My Job Is Not My Identity

A decade ago, I was at a party with a bunch of pro cyclists in Boulder (to be clear, not a humble brag—just a very common Boulder experience). Having just moved to Colorado from a lifetime in Western Pennsylvania, being around pro athletes in my very non-athlete body made me squirmy.

It was my first year at CU Boulder, and I was proud of getting into graduate school (even though, in hindsight, graduate school isn’t nearly as difficult as the doldrums of just workin’ a job). I loved being in situations where someone might ask, “What do you do?” and I could confidently respond, “I’m getting my Master’s degree!” Which was always followed by, “In what?” And then I’d get to excitedly explain that I was studying environmental journalism, storytelling, and digital media.

Sometimes, if I was feeling extra sure of myself—or if I’d had a particularly cool class that week—I’d expand on what I was focused on. Some weeks I was deep in neo-Kantian moral philosophy. Others I was tearing down the foundations of energy policy and crafting solutions to our national grid problem.

At this party full of pro-cyclists, standing around a parking lot in front of a bike shop, everyone was (unsurprisingly) chit chatting about bikes and bike things and bike speeds and bike parts. So when a guy casually asked (after I introduced myself and said what I did), “So, are you a writer then?” I stupidly heard, “Are you a RIDER then?” Which in retrospect would be a really fucking weird way to ask someone if they ride bikes, but with all the bike talk, I assumed that’s what we were on about.

“Oh, god no,” I remember saying with a lot of conviction, not wanting to be judged next to these intense bike people. “I’m not a professional or anything. I just ride for fun.”

“You can still call yourself a writer even if you’re doing it for fun,” he said, mishearing me as well.

OH A WRITER! I suddenly realized. But he’d already sauntered off, likely uninterested in someone who didn’t even have the chutzpah to identify herself as the thing SHE WAS LITERALLY STUDYING IN SCHOOL.

At that point in my life, I actually did call myself a writer quite often. I’d just had an essay published in the reputable literary magazine Terrain.org and it had been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. I was working as a reporter for the CU Boulder alumni magazine as well as a research assistant for the Ted Scripps Fellowship in Environmental Journalism. Sure, I wasn’t exactly making a living as a writer, but god dammit, I WAS A WRITER!

And then school wrapped up. I tried for months and months to get a job in my field and…nothing turned up. I finally took a job with a bike-shop marketing company (fitting, given where this story began) and suddenly, even though I was still writing nearly every morning before work, I no longer felt like a writer.

My identity shifted overnight to account coordinator.

When people asked, “What do you do?” I’d solemnly mumble, “I work in bike-shop marketing.” It felt like a lie to call myself a writer when professionally…I just wasn’t.

But the drive was still in me. I figured if I could pay my rent with this other job for a while, eventually I’d find a way to write full time.

But one thing led to another and before I knew it, I was an executive assistant, then a comms coordinator, a digital engagement manager, a comms manager, and then finally a comms director. What I thought would be a short stint in traditional work while I figured out what to do next became a decade-long climbing of the corporate ladder, always hoping the next rung would allow me to feel settled enough that I could return to my true writerly identity.

Without realizing it, 10 years had passed and despite thousands of hours of writing, and studying writing, and thinking about writing, I had completely stopped identifying as a writer at all.

Today, when someone asks me what I do, I usually say I work in conservation. Which is both true and noble—and fairly aligned with my degrees—but fundamentally not a genuine reflection of who I see myself as.

How We Define Ourselves

Identity is a fickle thing. On the one hand, it’s something we get to define for ourselves. On the other, it’s a reflection of how we actually spend our time.

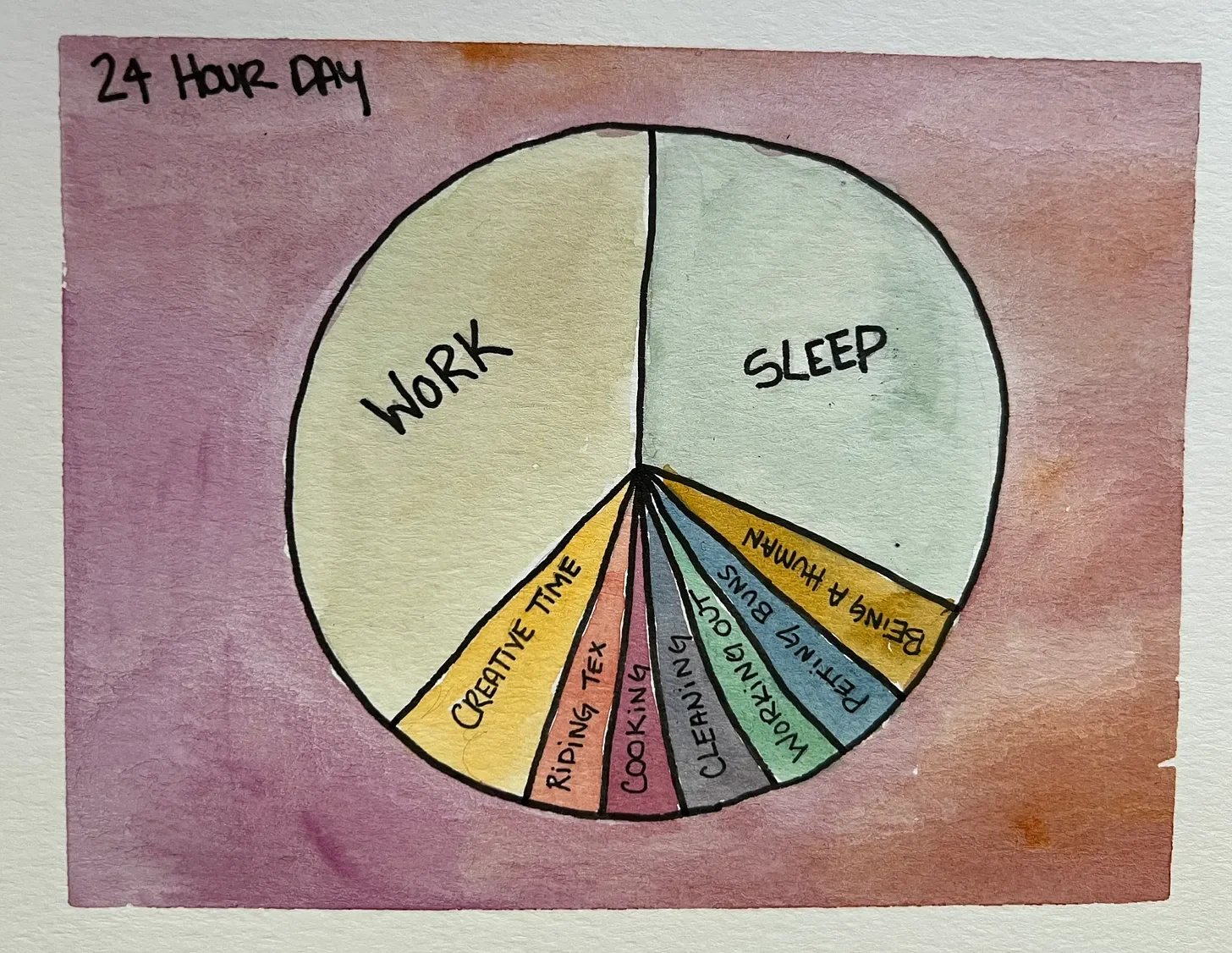

When eight hours of my day are taken up with directing communications (whatever the hell that means) and at best only one hour is filled with writing, it’s difficult to argue that writer should rise to the top. By that math, I could also identify as a chef, a house cleaner, a rabbit caretaker, or a horse trainer—since I do those things just about as often as I write.

I’ve learned recently (as in just this last month) that opening conversations by asking what someone does for work is a VERY American habit—and very frowned upon elsewhere.

From what I gather (non-Americans, feel free to call bullshit), in many other countries, what you do for your job is considered one of the least interesting things about you.

The Trap of “Workism”

When you look at how our systems are set up here—fewer social services, an epidemic of loneliness—it makes sense that Americans get caught up in what journalist Derek Thompson calls “workism.”

“[Workism] is rooted in the belief that work can provide everything we have historically expected from organized religion: community, meaning, self-actualization. And it is characterized by the irony that, in a time of declining trust in so many institutions, we expect more than ever from the companies that employ us—and that, in an age of declining community attachments, the workplace has, for many, become the last community standing.”

This might explain why Americans love to break the ice by asking what someone does for work. If there’s an assumption that work provides meaning and community, then knowing someone’s job tells you a lot.

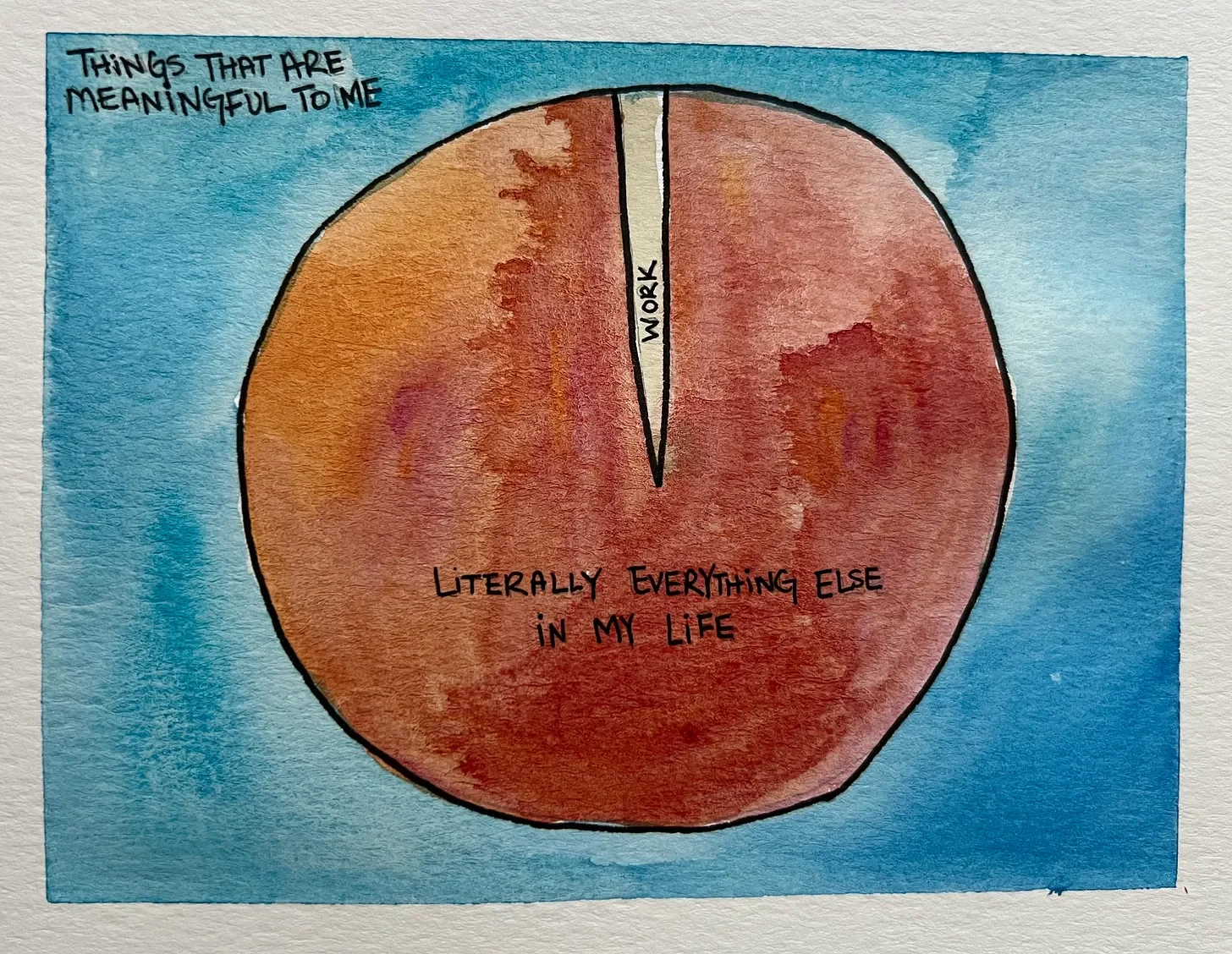

The problem is, my work doesn’t provide community, meaning, or self-actualization—nor do I want it to. Work provides a rent check. Work pays the board for my horse. Work ensures I only had to pay $50 for $4,000 worth of blood work (though tying health insurance to employment still feels absurd). Work gives me stability. And for that, I’m grateful.

But when measured in terms of “meaning” rather than “time,” work is a very insignificant part of my identity.

It’s why I feel close to emotional collapse anytime anyone wants to talk about careers lately. There are one million more interesting things about me. Could we please talk about those?

But I know I’m equally culpable. Just the other night I filled the natural lull in a conversation with a couple of new acquaintances by asking what they did for work. I regretted it instantly, but our culture is so primed for that question, it was coming out of my mouth before I even really knew what I was asking.

You Get To Decide Your Identity

I’ve been toying around with calling myself a writer and an artist when people ask the dreaded “what do you do?” question. The thought of saying that out loud makes me about as nauseous as answering the question “Do you believe in god?” did when I fully stepped away from religion at 19. (I’ve got the answer down now though: Yeah! SHE’S awesome! Really stops ‘em in their tracks.)

In all my career frustrations, I’m beginning to feel this mental shift in identity is far more important than, say, finding an entirely new career. I think at the end of the day, I’m always going to be a little (or a lot) disappointed that my job isn’t an accurate reflection of myself. Of course there are jobs that would likely get me closer, but rather than spending years of my life crafting a new career, I’d rather just spend that time, well, crafting.

There were plenty of dudes in my undergraduate fiction classes who called themselves writers as they churned out one unpublishable sad boy short story after another. And honestly, good for them. Perhaps we all need a little more 19-year-old–boy-in-their-first-fiction-class confidence.

For now, my answer to “What do you do?” will probably be: “I’m a writer, working on a book proposal. But I also work in conservation.” It satisfies the American curiosity about how I pay my bills without centering my 9–5—or making me sound like a total twat.

And I’m committing to asking other people anything but what they do for work. EVEN THOUGH I AM CURIOUS. Instead, I’ll ask about hobbies, the books they’re reading, or the podcasts they’re jamming to. Those things sound much more delightful.